The death of Pope John Paul I, Conspiracy or not?

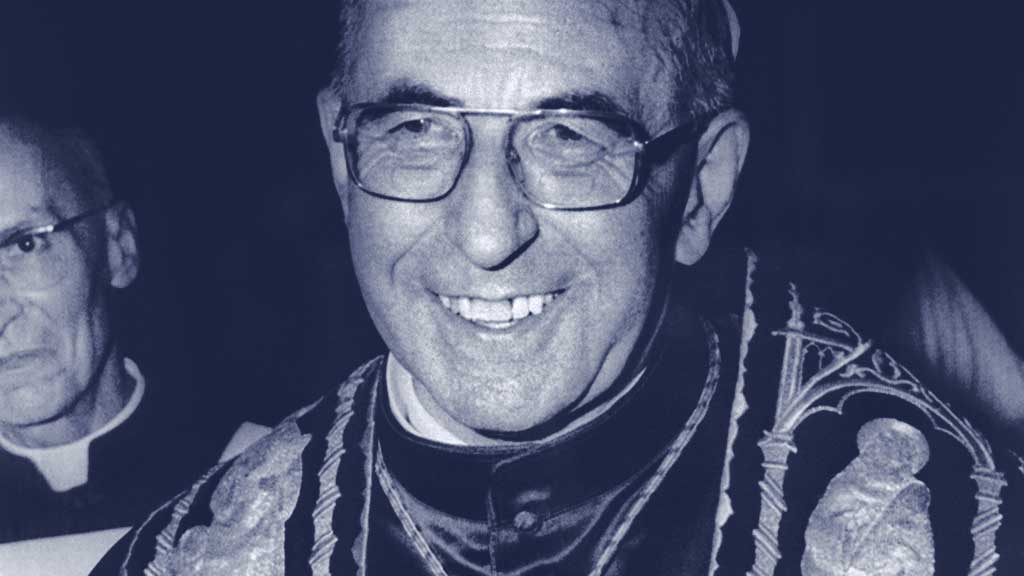

Even in Italy, land of the conspiracy, no plot comes more entangled than the death of Pope John Paul I. When white smoke puffed above the Vatican on 26 August 1978 to signal the election of Albino Luciani to the papacy no one was more surprised than Luciani himself.

A Vatican low-profiler, Luciani was a deeply modest man, who refused the papal tiara at his coronation and endeared himself to many, not just Catholics, by his smiling kindness. Just 33 days later, he was dead.

Natural death?

According to the Vatican, John Paul I’s death was natural. But then they would say that, wouldn’t they? Suggestions that the new pontiff’s demise was anything but natural circulated immediately. Fuelled by the easily disprovable lies and oddities emanating from Vatican itself:

At first it was announced that John Paul had been found dead in his bed, with a copy of Thomas a Kempis’s Imitation of Christ propped before him, by his secretaries Magee and Lorenzi; in fact, the body was discovered by a nun, Sister Vincenza. The Vatican blamed John Paul’s untimely death – he was 66 – on his heavy smoking. But he didn’t smoke.

A false time of death was issued. Most controversially of all, a post mortem was not conducted because, insisted the Vatican, post mortems on pontiffs are prohibited by Vatican law. Yet a post mortem had been conducted on the remains of Pope Pius VIII in 1830.

Within 24 hours of his death John Paul I was embalmed. John Paul I had enemies as well as friends. David Yallop, in In God’s Name (1984), identifies Vatican reactionaries, Freemasons, and Mafiosi as an unholy alliance which loathed the new Pope – loathed him enough to murder him by the administration of digitalis to initiate a heart attack. According to Yallop, the liberal John Paul I was intending to soften the Catholic position on contraception, thus raising the ire of Vatican conservatives.

Propaganda Due

The Freemasons of Propaganda Due (P2), meanwhile, feared a papal expose of their secret caucus inside the Vatican. More worried still were the Mafiosi, who believed that the new pontiff was intending to clean up the Vatican Bank. Something had long been rotten in the state of the Vatican’s banking system.

In the aftermath of the Second World War, Vatican bank officials had laundered money filched by some close to the national socialist regime, as well as setting up “rat lines” for alleged German war criminals to escape to South America. When the ‘Nazi Gold’ dried up, the Vatican banks, especially the Istituto per le Opere Religiose (IOR), became moneylaunderers for the Mafia.

The Mafia

The key figures in the IOR’s money-laundering for the Mob were Roberto “God’s Banker” Calvi, director of the IOR’s Milan-based outlet Banco Ambrosiano, and, allegedly, Archbishop Paul Marcinkus. Michele “The Shark” Sindona, a Sicilian financier, was, in Yallop’s scenario, the linkman between the bank and the Mafia.

If the Vatican Bank’s corrupt officials were dismissed, the Mafia would lose a favoured means of disposing of its ill-gotten gains. The Pope had to go. In Yallop’s scenario, the murder of John Paul I worked out nearly perfectly, since he was replaced by John Paul II, who was socially conservative (thus opposed to contraception) and who, far from cleaning up the Vatican Bank, gave Archbishop Marcinkus immunity from prosecution.

Yallop’s case, though strong, is circumstantial. The Vatican Bank was corrupt to the core. And one of the major players, Roberto Calvi, met a retirement not usually associated with the banking profession. See other post: Who killed Calvi?

Who killed Calvi?

But did John Paul I himself meet an unnatural death? A persuasive counter-blast to Yallop’s book came in 1989. And John Cornwell, an English journalist wrote A Thief in the Night, after conducting his own investigation. Cornwell concluded that John Paul I died of a pulmonary embolism.

Indeed, John Paul I had manifested the classic symptom of the condition: swollen feet. Of course, it might be objected that John Cornwell would say that, wouldn’t he?

Indeed, John Paul I had manifested the classic symptom of the condition: swollen feet. Of course, it might be objected that John Cornwell would say that, wouldn’t he?

The Vatican asked to write A Thief in the Night.