Wagner’s mythic medievalism and Teutonic underworldliness was shared by the English Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood’s embrace of William Blake’s prescient dictum—Gothic form is living form—the largely unacknowledged creed of Victorian architectural revival.

Barbaric

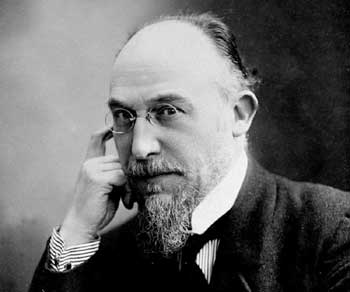

An adjective that had once meant “barbaric,” “Gothic” had been redeemed by perception of the medieval Catholic Church’s architectural embrace of the divine-maternal, the mysterious, tempting curve: the very essence of art, according to Edmond’s Bailly’s bookshop habitué, art critic, aesthete, monarchist, and Catholic Decadent Joséphin Péladan.

Ogives

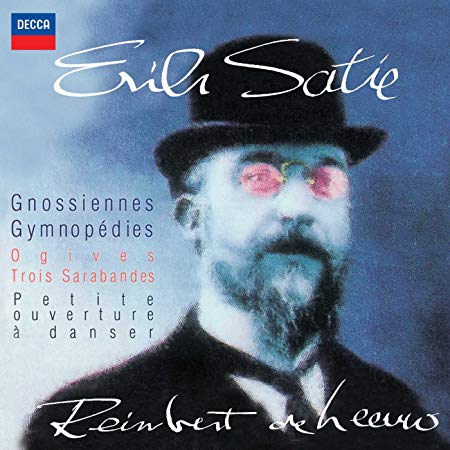

Erik Satie released his Ogives in 1889: four piano pieces inspired by the curves (ogives) outlining Gothic arch windows in Paris’s Notre Dame cathedral on the Île de la Cité.

Combined femininity and austere spirituality formed a window through which we may pass into the light, as to, and through, a symbol, like penetrating an icon of Orthodox devotion: journeying from the organically visible to spiritual vision.

A window

A window, of course, works both ways. We see through it as light comes simultaneously through it to us. The visitation of light is suggestive of another world. The bright sky is a symbol of infinity, of boundless values and epic, fraternal ideals.

Yet the Symbolists preferred autumnal light: hinterland between the known and the unknown, the clear and the obscure, twixt presence and absence, between life and death. Who are we? Where do we come from? Where are we going? Melancholy, longing, nostalgia were preconditions of illumination.

Listen to Erik Satie’s Ogives No.1 (performed by Reinbert de Leeuw)

Symbolist

For the Symbolist, Nature, ordinarily viewed, was naught but superficial sense impression, a mirror: mere flesh, not spirit or animating mind. Through a genuine icon, on the other hand, imagination enabled the meditative viewer to slip via the locked gate of the opaque image to the mystery of being.

Nobody who has made this journey can see the world as he or she saw it before, nor will be content any longer with the superficial, the shallow reality of the materialist that is conditional, not absolute.

Illumination

Such illumination was eagerly lapped up, if not always fully understood, by Symbolists; its nectar Parnassian, no . . . Olympian and Heliconic, for from the invisible summit of the loftiest poetry came the perspective to see, judge, dismiss, or discriminate and—who knows?—even to transform the huddled, distasteful world below, whose blackened state might yet be subjected to the gold-making skills of the alchemist, that is to say, “Artist.”

Rimbaud wrote of the “alchemy of the word.” Poetry and painting were never so close as they were among Symbolists: necessarily esoteric, magical in the embrace of the supernatural, occult in penetration of the image.

Ideal art evinced a trove of gold existing beyond the world’s material image. Those who understood were initiates; thus Péladan and his colleagues embraced Leonardo as an initiate, a “Grand Master.”

Péladan’s declarations about the divine Leonardo are the precise source of the potent Da Vinci Code myth.

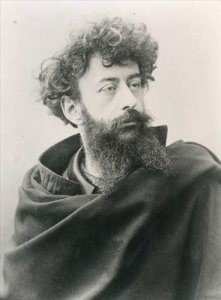

Joséphin Péladan (28 March 1858 in Lyon – 27 June 1918 in Neuilly-sur-Seine) was a French novelist and Martinist. His father was a journalist who had written on prophecies, and professed a philosophic-occult Catholicism.

He established the Salon de la Rose + Croix for painters, writers, and musicians sharing his artistic ideals, the Symbolists in particular.

https://amzn.to/2Izrb2E