After six years of war, the Rhineland-Westphalian 6th Infantry Division was no more, its members either scattered to the winds or marching the long trek to Siberia. Those who had availed themselves of the opportunity offered by their general to attempt to escape to the West soon questioned the wisdom of their choice.

As they climbed over mountains, swam across rivers, and slithered through forests, they found themselves to be hunted animals—animals with a bounty of 25 Reichsmarks on their heads, dead or alive. Some were captured by Russian soldiers, who had lost some of their lust for German blood now that the war was finally over.

Instead of a “G’nickschuss,” the captives were promptly relieved of watches, rings, and money, and sent off to join their comrades on the march east. The fate of others, tracked down by Czech partisans, depended on whether the partisans preferred to drag in a dead German for the bounty or march him back to the Soviet authorities under his own power.

Incredibly enough, some of Brücker’s men did succeed in evading the Russians and partisans and reached the West where they either surrendered to the Americans or simply cast away their weapons and uniforms, blended in with the thousands of civilian refugees, and returned home.

Hauptmann Erpenbach and most of his battalion, Major Pflugfelder and Hauptmann Freiherr von Weichs with part of the artillery regiment, Oberleutnant Eckhard and a few members of the divisional staff, and Leutnant Josef Dollmeier of “Hetzer” fame were among those who avoided Soviet captivity.

POW

But even those who had managed to surrender to the Western Allies could not rest entirely easy. Stalin was demanding that those German soldiers, now in British or American hands, who had fought in the East be immediately turned over to the Red Army. Except for those unfortunate Soviet nationals and those of the Baltic States who had fought alongside the Germans, Stalin’s demands were largely ignored. The Western Allies kept their German prisoners, and Stalin kept his.

Although at times rations were sparse, German prisoners in the West were for the most part spared brutal treatment and humiliation. After what many of them had endured during the war, an empty stomach, occasional kick, or insult from an aggravated guard were hardly things about which to complain. Some prisoners were released in months; for others, confinement was longer, but by 1947, the majority of German prisoners had been sent home.

But what was home? Cities and towns reduced to rubble, 3 million dead at the front, 3 million civilian dead, millions of homeless refugees, hunger, humiliation, despair, defeat. Is this what they had fought and died for? Then came the revelations of the horrors of the camps and the crimes of the Nazi regime: Auschwitz, Dachau, Bergen-Belsen, mass deportation, mass extermination—the criminalization of a nation. Is this what they had fought and died for?

Auf nach Siberien

There was no answer. So they got on with the daily struggle to survive amid the physical and spiritual ruins of the Reich, and when the times improved, they got on with life—jobs, family, a future. They rebuilt their nation, they rebuilt their lives, and the past was left behind, repressed and forgotten, never to be revived.

Those members of the 56th Infantry Division who had not escaped to the West joined the endless columns of plennis (prisoners) trudging east. Despite the cynical phrase “Auf nach Siberien!” often repeated among the German prisoners, few actually found themselves exiled to that frozen waste. Most were sent off to the hundreds of camps west of the Urals and put to hard labor. Once again, the Eastern War had reverted to a more barbarous age when those of a vanquished tribe who were not slain were marched off by their conquerors into slavery.

The condition of the German prisoners varied with the camp, the day, or the guard. When sent out in the morning to labor, one did not know if one would survive the day. Of the 3.4 million German soldiers in Soviet captivity, 1.5 million died from hunger, disease, overwork, or execution.

However, in the main, their deaths were more the result of indifferent neglect rather than intentional cruelty. To the Soviets, with one-third of their nation laid waste and 20 million of their own dead, the life of a single pathetic plenni or for that matter a thousand plennis was of little consequence.

Soviet Labor camps

The labor was hard, the climate harsh, the food less than adequate—500 grams of bread per day and a thin barley soup that the captives christened “blauer Heinrich” due to its blueish color. Then there was the “re-education” or rather attempt to brainwash a literally captive audience to the “more just” communist system. Members of the Antifa descended upon the camps and conducted endless lectures, with no great successes.

The plennis had seen with their own eyes the “justness” of Bolshevism and wanted no part of it. Besides, starving, exhausted men are hardly receptive to long-winded discussions of political and economic theory. Of course, there were those who, for a bit more bread and a few more grains of barley in their soup, did cooperate with their captors, but they were quickly shunned and ostracized by their comrades and would continue to be so long after their release and return to Germany.

Despite Soviet attempts to sow political discord among the prisoners and drive a wedge between the men and their officers, the captives held solidly together. The “unshakable bond between officer and man,” expressed in von Hindenburg’s proclamation a decade before, remained firm as the German soldier strove to prove his soldierly superiority even in captivity.

Discipline

Some Soviet camp commanders, particularly those with front-line experience, were wise enough to recognize that a camp with a body of well-disciplined prisoners ran much smoother, and rather than wasting time on indoctrination and creating discord, actually encouraged the prisoners to continue wearing their badges of rank and maintain order and discipline in the well-respected Wehrmacht fashion.

Purgatory, however, was not indended to be forever and so it was with the purgatory of the Soviet labor camps. As early as 1946, nearly a million German prisoners had been released from Soviet captivity, but not for any humanitarian reasons. They had been judged too ill or weak to be of any use as slave laborers.

Over the next few years, more prisoners were sent home, sometimes a flood, sometimes a trickle, seemingly without rhyme or reason. Others, mostly officers or prisoners of particular interest, languished on. To provide a façade of legal justification for not repatriating German prisoners of war, the Soviets held mock trials in which the verdict was always “guilty,” and the sentence, a uniform twenty-five years hard labor.

Return home

But eventually, even those so convicted were released. In 1955, the Chancellor of the new state of West Germany, Konrad Adenauer, travelled to Moscow and secured their freedom. After ten years, the last German soldiers came home from the war.

But what was home? A new Germany. A modern Germany. A democratic Germany. No Führer, no war, no streets filled with rubble and corpses. Instead, the streets bustled with well-dressed and well-fed people—people in a hurry for they had somewhere to go. As the former prisoners or “Spätheimkehrer” shuffled through the noisy and busy streets, they stared around in wide-eyed astonishment as though visitors from another planet.

Now and then a passer-by would glance at these pathetic creatures with their ragged uniforms and hollow faces—uniforms of a forgotten past, faces of a forgotten past, a past now suddenly brought back. Embarrassed, the pedestrian would quickly look away and rush by.

6th Infantry Division Reunions

Eventually even these “Spätheimkehrer” were able to adjust to this new post-war world, and the Rhineland-Westphalian 6th Infantry Division, which a decade ago had been scattered to the winds by defeat, was now scattered to all corners of Germany by peace as the old “Ostkämpfer” got on with their lives and left the past behind.

In time, though, they found one another again. A chance meeting on the street; a face, though middle-aged, still vaguely familiar; a flash of recognition and the sudden rush of memories. Then an afternoon in a Bierkeller—the office could wait. Then on into the evening, Frau und Kinder could wait. As with veterans of any war, of any nation, there does come a time when enough years have passed to dull the sharp edge of the horror and the pain so that the past, rather than repressed, can be revisited.

Kameradschaftbünde (Comradeship associations)

And so it was with the Rhinelanders and Westphalians. Contacts increased. Comrades thought long dead were discovered to be alive. Informal get-togethers grew larger and occurred more often until the decision was made to formally establish the regimental Kameradschaftbünde or veteran organizations and hold yearly reunions in the division’s old garrison towns throughout the former Wehrkreis VI.

Throughout the ’60s and ’70s and on into the ’80s, the veterans of the 18th, 37th, and 58th Regiments held their reunions, often meeting in the same barracks where they had first put on the “graue Rock” and marched off to war. The beer flowed freely as did the memories. Memories of fallen comrades: Schnitger, Rindfleisch, Küster, Hellweg. Memories of the winter, the victories and retreats of Rzhev, Bobruisk, the Warka, and Lauban. They looked back on all they had endured, on all they had achieved, and shook their greying heads in disbelief—Mein gott, could they have really been that young and reckless of life?

Memories

There were also memories of what to them represented “lighter” moments—the impromptu trench raids and the racing back to their trenches dragging along whatever war trophies they had grabbed. Now they could laugh at the insane risks they had taken. Or how on New Year’s Day they had always sent Ivan diving for cover with their customary greetings of ordnance. Then there was the time at Lauban when they had stolen Ivan’s tanks right out from under his nose.

The high point of these regimental reunions was the occasion when the Kommandeur was able to attend. The shout would go up, “Der Alte ist da!” and as in the old days, the “Vater” of the regiment would review his troops, who stood as upright and stiff as their aging limbs allowed. He would slowly pass them by, one by one, eye to eye, and the bond between officer and man was renewed yet again.

Also renewed at the reunions were the bonds with their fallen comrades, who lay beneath the Birkenkreuzen in graves from the Loire to the Volga. The list of the gefallenen was read out. The list was long. The regiments each counted over 3,000 of their ranks as dead or missing, and now decades after the war the surviving Landsers knew that their missing comrades were never coming home.

Their bones lay lost and moldering somewhere in the East. Nor did this reflect the total cost of duty. For the many and varied units that had fought in the ranks of the 6th Infantry Division during the last desperate battles in Silesia, there would be no accounting. Their names and fate would remain forever unknown.

Old Veterans vs young soldiers

The Kommandeure, the aging veterans, and their fallen comrades were not the only ones present at the reunions. The new German army had revived the custom of “tradition-bearer” with units of the Bundeswehr being entrusted with maintaining the memory of certain regiments of the former Wehrmacht. (In the case of the 18th Regiment, the tradition-bearer was the 213th, later the 214th Panzer Battalion.)

The tradition-bearers often attended the reunions and although respectful of these war-hardened veterans surrounding them, there remained a certain uneasiness with the relationship. The old veterans were often asked by the young soldiers, “Why did you continue fighting so long for the criminal Nazi regime? Why didn’t you simply desert?”

Germany’s forsaken sons

Though perplexed by such questions, the old warriors tried their best to explain—but in vain. They were speaking across a generational and cultural divide. How could an old “Ostkämpfer” possibly explain a Rzhev, a Kursk, a Warka, or a Silesia to a younger generation—a generation raised in a prosperous, free, and democratic Germany? A generation that had never known war or the iron bonds of comradeship forged in battle? The answers given were as incomprehensible to the young recruits as the questions had been to the old warriors. As German soldiers, they had fulfilled their duty to Volk and Vaterland wie das Gesetz es befahl—obedient to the law. Did that not say it all?

To them, perhaps, but the world would never forgive them. To the world, they were Nazis all and thuggish murderers. Even their own children looked upon them as criminals or, at best, a primitive brutish species, thankfully, on the verge of extinction.

With the next generation of Germans, the generational gulf grew wider, the condemnation stronger, the alienation greater. They had become “die verlassenen Söhne” (“Germany’s forsaken sons”), who, having been condemned by their parents’ generation to fight the Führer’s wars, were now condemned by their children’s generation for having fought the Führer’s wars.

Duty, sacrifice, obedience, loyalty,

There was nothing more they could say. Their words of duty, sacrifice, obedience, loyalty, fell upon a society whose ears had long since been deafened by the narcissism of prosperity and the illusion of security. So they fell silent and over the years, one by one, joined their fallen comrades, leaving their story to be told by a stranger.

Accusations—explanations; condemnations—justifications still fly back and forth across their graves as accusers and defenders attempt to score their points. Let the debate rage for it touches them no longer. They alone knew who they were, and of that there is no debate. They were, simply put: “Soldaten bis zum letzten Tag.” Soldiers to the last day.

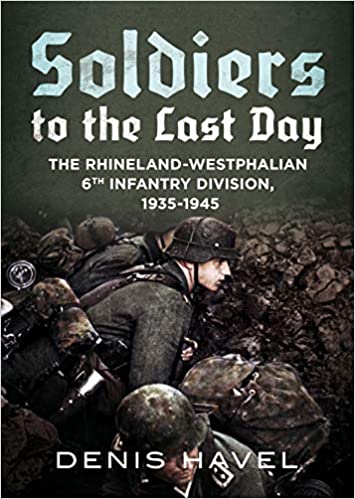

src. Epilogue Soldiers to the Last Day: The Rhineland-Westphalian 6th Infantry Division, 1935-1945

This book is the history of the Rhineland-Westphalian 6th Infantry Division. Among the first divisions created by the Wehrmacht in 1934, it went on to establish one of the longest and bloodiest records of continuous combat of any division during the war—Allied or Axis. Engaging in its first combat within weeks of the outbreak of World War II, the division fought literally to the last hour of the war.

Although it won its first laurels in the French campaign of 1940, the division received its reputation as one of the best three divisions of the Wehrmacht while on the Eastern Front as it engaged its Soviet opponent in combat, the extent and savagery of which has yet to be fully appreciated by Western analysts.

This present work recounts not only the story of the Rhineland-Westphalian 6th Infantry Division but, perhaps more important, that of the men who served in its ranks. Their story is told not from the author’s objective point of view but from theirs—from the general down to the common Landser, neither of whom had the luxury of detached objectivity.

In a similar vein, the story is presented in the spirit of the times in which it occurred, leaving intact and without comment or condemnation the attitudes, beliefs, impressions, and emotions as well as the prejudices and misperceptions prevalent during that period.